If your time is short:

|

In FDA-regulated manufacturing, genuine human errors do occur, but they’re cited far more frequently than they probably should be.

In truth, most problems that appear to be caused by human error — especially those that occur multiple times — are actually rooted in processes or systems that when left unchanged, will keep producing the problem despite the convenient band-aids often placed over them.

When human error is identified more frequently than it should be expected to happen, it signals to investigators that problems aren’t being internally investigated thoroughly enough. This can quickly shift the investigator into problem-hunting mode and open your quality management system up to even greater scrutiny.

Read Also: What The FDA Expects from Your CAPA Process

But what about the rare instances where one-time errors are made by otherwise well-trained personnel following well-defined processes? A moment of inattention due to a passing distraction can lead to serious problems. In these cases, the human error classification may be justified after a thorough investigation reveals nothing in every possible place there is to look.

Again, this conclusion should never be jumped to as a convenient way to avoid the important work of problem-solving. It should only be considered a viable justification when every other possible cause has been exhaustively explored and eliminated.

Grab our free white paper and learn more ⤵

The Guide to CAPA & Root Cause Analysis in FDA-Regulated Industries

A Model for Analyzing Human Error

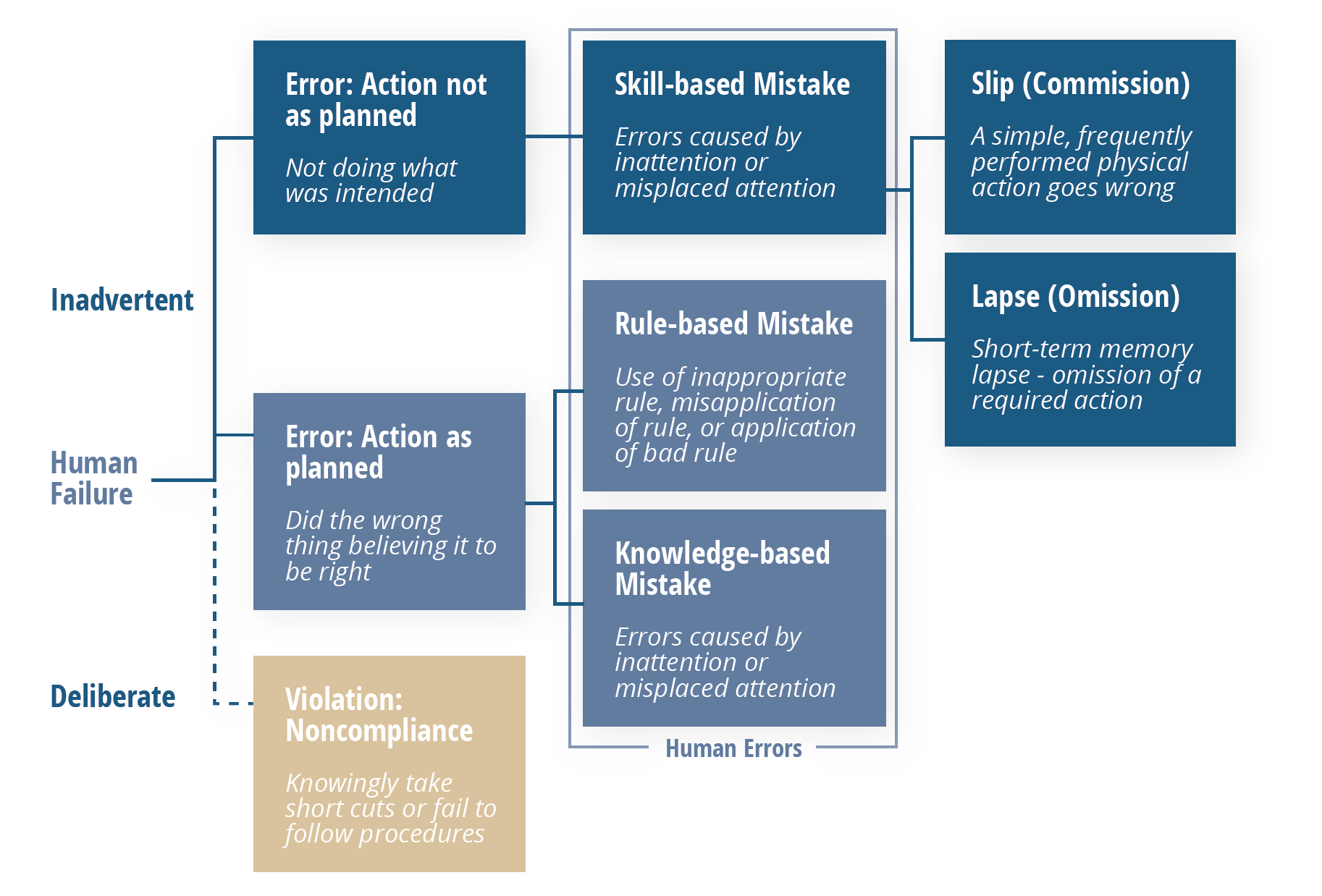

Given this caveat, it’s helpful to arm yourself with a model for analyzing what might appear to be human errors in order to determine whether actions (or inactions) were deliberate or inadvertent. The outcome can help you determine whether or not human behavior really is to blame as well as where you might expect to find a problem elsewhere (such as inadequate training, poor SOPs, etc.) if the root cause appears to be less human than you initially thought upon further analysis.

Enter the Skills, Rules Knowledge/Generic Error Modeling System illustrated below. It’s relatively simple, but offers a reliable way to tease out genuine human errors from other problems while pulling real human errors apart even further to reveal their motivating factors.

Following this model, errors that are shown to be “inadvertent” can be considered genuinely “human,” which then fall into one of three categories: skill-based, rule-based, or knowledge-based mistakes.

Those that are skill-based can be broken down one more time, into either a slip or a lapse. Both of these point to the same root cause: a lack of attention, which manifests itself in two different ways: momentary memory loss or a routine action that wasn’t performed.

Once more, it’s important to note that these type of errors should not be happening frequently. The vast majority of problems that appear to be human error at first should lead you elsewhere upon further analysis.

Errors shown to fall into one of the two other categories should be viewed through a different lens. In these situations, processes—particularly related to training and oversight should be scrutinized as contributors as explained in the breakdown below.

Knowledge-based Errors

These types of errors occur when someone was multitasking beyond their limit, or were otherwise unable to devote the focus required to accomplish multiple tasks at once. In this situation, identify why the person was multitasking in the first place. The root cause likely lies here.

- Were they tasked with doing too many things at once?

- Is that department under-resourced?

- Was this individual’s supervisor aware that the person is multitasking beyond their limit?

Rule-based Errors

These errors are more technical in nature, such as someone applying an incorrect rounding rule which ultimately generates an out-of-specification (OOS) result. In this situation, rather than faulting an individual’s judgement, which may not be at fault, question why the person wasn’t adequately prepared to perform the task correctly.

- Did they receive insufficient practice in training?

- Did practice actually reflect the the operations they were performing on the floor

- Does the procedure specify the details to the degree they need to be explained in order to be performed correctly?

Two Places to Look for Systemic “Human” Errors

When errors are revealed to be less “human” upon closer examination, start asking questions that cast light on how the type of work in question is actually being done. This may lead you to discover the problem may be more serious and widespread, particularly in one of two areas summarized below.

Documentation

FDA-regulated manufacturing operations are followed by documentation every step of the way. If human error is found, take a hard look at your written records and ask the questions of them listed below. The real problems may lie in your processes for creating, maintaining, and distributing the documentation that drives your quality system.

- Are change processes long and cumbersome?

- Are your staff working with out-of-date or obsolete SOPs?

- Are your SOPs readily accessible? Can employees easily navigate to them and understand the information they need?

Culture

One of the best ways to immediately enhance quality throughout your organization is to realize most of the problems being described as human errors are something else entirely. Rather than using it as a convenient stand-in for thorough investigation, use human error as an opportunity to improve your company’s problem-solving processes. Fast closure rates of inaccurate deviations don’t demonstrate efficiency, just misguided values in the problem-solving process itself.

Replace this metric with a trending reduction in total deviations over time. The size of your backlog and closure times are functions of each other and should be handled accordingly. Keep in mind that the lack of a backlog will likely lead investigators to look at your closure trends. If your deviation backlog is reduced significantly in the weeks leading up to their arrival, they’ll know your methods were rushed rather than being a natural component of your QMS.

Next Steps

- Conduct an objective assessment of your internal problem-solving processes (ideally with the help of an experienced third party) and remediate accordingly.

- Replace metrics that establish problematic incentives with goals focused on long-term trending.

- Explore ways to improve problem-solving within your QMS to reduce backlogs while thoroughly investigating issues.

Grab our free white paper and learn more about effective CAPA and root cause analysis in FDA-regulated industries.